A solo exhibition of works by the Turkmen artist Nurridin Niyazov is currently on display at the Exhibition Center of Fine Arts of the Ministry of Culture of Turkmenistan. For the exhibition, the artist prepared a catalog in which he presented five copyright certificates related to research on the works of Leonardo da Vinci and other artists of the Renaissance era.

In 2018, at the Mahpirat Institute of the History of the Peoples of Central Asia (Tashkent), Nurridin Niyazov was awarded the title of Honorary Academician for his research work in art history by the decision of the presidium of the TURON Academy of Sciences. In the International Year of Peace and Trust, this fact arouses special interest in society.

In a conversation with Nurridin Burkhanovich, we noted that art historians who become artists are quite common, but artists engaged in art history are practically nonexistent. We asked him the question:

– How did it happen that you, a sought-after artist, became passionate about research work? And why did the genius of the Renaissance era, Leonardo da Vinci, become the object of your research?

– My love for art history, especially for the works of Leonardo da Vinci, developed in me during my studies at the Republican Art College in Dushanbe under the influence of the remarkable teacher Elizaveta Tatarenko.

In 1974, I was lucky to see the original masterpiece "Mona Lisa" by Leonardo da Vinci! I was passing through Moscow and learned that Leonardo da Vinci's "Mona Lisa" was exhibited at the A.S. Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts. The queue of people eager to see the original of the world's most famous painting was incredibly long. And it so happened that that day was the last day of my stay in Moscow—my ticket to Leningrad (now Saint Petersburg) was for the next day. Fearing that I would not make it to the museum before closing, I was very nervous and asked people to let me skip the queue. But everyone pretended not to hear me. Suddenly, a young woman handed me a token and said, "Take it—I can see the 'Mona Lisa' another day."

I waited for another hour and a half. Finally, I approached the painting. I was taken aback. It seemed not that I had come to her but that she had come to me in the image of a gypsy fortune teller. She was looking at me as if saying, "Solve my mystery!" I had heard before about the enigma of the Gioconda. Now I felt it firsthand. I stood in front of the portrait, staring without looking away. She looked at me as though we were alone in the world. I felt joy from her mysterious smile and at the same time disappointment from her stern, browless gaze.

– Your impressions of the original "Mona Lisa" obviously deepened your interest in Leonardo da Vinci’s works. But how did the desire to begin research work arise?

– Again, the cause was "Mona Lisa." Here's what happened. One day, I decided to make a copy from a rather good reproduction of her portrait and divided the reproduction into a grid. I was amazed to see several small pictures within the grid cells. It was these hidden images that sparked my passion for research. Over the course of my creative work, I have created twenty-five paintings in the cycle "The World of Leonardo da Vinci" and written eight art history articles. In 2014, my solo exhibition titled "The Secret of da Vinci" was held in Ashgabat.

– Nurridin Burkhanovich, could you please popularly tell us about your most interesting research?

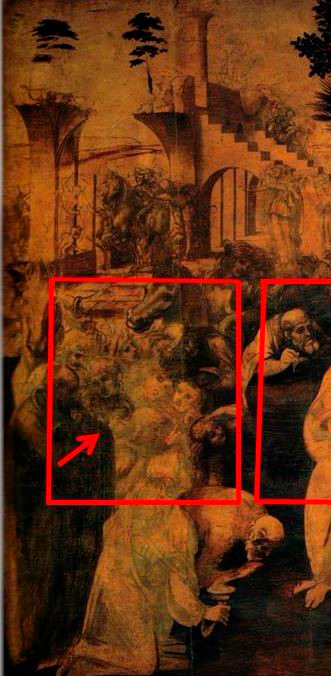

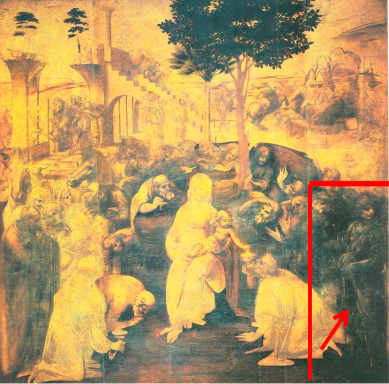

– Take, for example, Leonardo da Vinci's painting "Adoration of the Magi." If you look closely, on the left, you can see another "Adoration" scene. It also depicts Madonna with the infant. But no one worships them; instead, a strange priest above is bowing and blessing them.

On the right, in the foreground of the painting, there is a figure of a young man that draws attention. In V.N. Lazarev's book, it is mentioned that some researchers claim this is a self-portrait of Leonardo. However, this version is considered controversial. I present three facts supporting its truthfulness. First: the figure of the young man is portrayed in deep shadow at the right edge of the painting. Unlike the main actors in the foreground, the young man faces opposite to Mary and the infant Christ. This confirms that Leonardo was a non-believer, as many around him said.

The second fact: there is a supposition that Andrea Verrocchio—Leonardo’s teacher—when creating the bronze sculpture “David,” gave it the face of his young student. However, there is no documentary evidence for this supposition. Among more than seven thousand drawings by Leonardo preserved to this day, there is not a single one relating to his youth.

Nevertheless, I believe the hairstyle of the young man in the painting "Adoration of the Magi" can serve as proof of this legend, as it is very similar to the hairstyle of Verrocchio’s “David.” The third fact: if one compares the portrait similarity of the bronze "David" with the face of the young man in "Adoration of the Magi," one can find convincing resemblance considering the age difference of over ten years. Probably, this way of depicting a self-portrait Leonardo adopted from Sandro Botticelli. Botticelli, for instance, in his "Adoration of the Magi," painted a young man in a yellow cloak at the forefront on the right edge of the painting. Most researchers consider this figure a self-portrait of Sandro Botticelli.

– What was the purpose pursued by Renaissance artists applying the method of hidden images?

– There is an explanation for this: most paintings were made on religious subjects, and at that time, depicting anything extraneous in religious-themed paintings was punished by the Inquisition court. Leonardo was always inclined to secrets and mysteries, so the method of hidden images was acceptable to him. Moreover, generations of young artists after Leonardo, such as Raphael, Filippino Lippi, and Giorgione, also applied this method.

– How would you like to conclude our conversation?

– In 2022, I received copyright certificates for brochures on the research of some works by Leonardo da Vinci. The legendary fame of this artist has outlived centuries, and over time it not only does not fade, but burns even brighter. Discoveries by modern science repeatedly fuel interest in his engineering and science-fictional drawings, in his encrypted writings. And surely, soon we will learn the answers to all the coded secrets to which researchers of Leonardo da Vinci's work point. I will be happy if my research on Leonardo da Vinci’s works becomes a contribution to the common treasury of art history.